How do we talk about acculturation and about adjusting to a new culture? There is a simplistic either/or view of acculturation which takes the attitude that a person is either American or …(fill in the blank: French, Vietnamese, Chinese, Indian, Russian, etc..) that does not really capture the full picture of how a person adjusts to a new culture. In this post I’ll introduce a more nuanced model of acculturation that better describes how different people adapt and adjust to a different culture than the one they grew up in.

Culture

Merriam Webster has six different definitions for the word culture. The meaning I use on this website is:

Culture: the beliefs, customs, arts, etc., of a particular society, group, place, or time

Culture is something that surrounds us, that we live in like a fish lives in water. We usually take our own culture for granted until some event makes us realize that our beliefs about the world and how to behave in it are not shared by every person. That event exposes us to another culture. Obvious examples of such an exposure are moving from one country to another, such as migrating from Asia to the US, or from Germany to France. Other examples may be interacting with a different group, where “different” refers to a difference in ethnicity, race, class, religion or age. For minority or immigrant families, just stepping out of one’s home into the public space results in exposure to another culture.

Acculturation stress

It is a challenge to move from one culture to another. In the new culture, we are exposed to new values, beliefs and behaviors and we are changed by them. Beliefs we hold are possibly not taken for granted anymore. Who we are may be questioned. What is important to us may not seem so important anymore. Our behaviors may change. We have emotional reactions to the cultural change. The stress that results from the cultural change is called acculturation stress. This stress can be positive (the person enjoys being in a new environment and looks forward to learning and adapting) and negative (the person is overwhelmed by all the changes). Many factors play into acculturative stress and the possible intensity of stress experienced by the individual: how similar and dissimilar the two cultures are, whether the contact is voluntary or not (for example, choosing to emigrate as opposed a forced relocation), whether the contact is permanent (immigrant versus international student). If we are talking about immigration, the person’s migration experience (simple plane travel as opposed to fleeing at the risk of losing one’s life), the difference in status and life conditions in the country of origin and in the host country, and changes in family structure all contribute to the migration and acculturation stress.

Adjusting to a new culture

Let’s talk about a hypothetical individual who has moved, say, from Asia to the US. Let’s make the person a woman. I could also talk about an adult male moving from Germany to the US, but for this discussion, let’s assume a female adult, named Lily, whose family moved from China to the US.

One way of thinking of how Lily adjusts to the mainstream American culture is to ask: “How Chinese is Lily?” “How American is she?” As a way to address these questions we might look at: how much English does she speak? How much Mandarin? What foods does she eat? What books does she read? What TV shows? Who does she hang out with? What are her attitudes and values? and many other such questions. These questions are used to notice how much has Lily taken on the American culture and how much she holds on to Chinese culture.

A simplistic way of thinking of Lily’s acculturation opposes the question “How Chinese is Lily?” to “How American is she?” The assumption is that Lily is either Chinese, or American, or somewhere in between, and that a person is either Chinese or American, but not both. This way of thinking assumes that immigrants such as Lily assimilate into the mainstream culture of the US. It is a one dimensional model.

However, to look at Lily’s adjustment to the US only in terms of how “American” she may be misses an important part of her cultural experience. Lily may be Chinese in some ways and more American in others; she may be more Chinese with her family, but more American with her peers. She may consider herself to be both Chinese and American, or neither.

Berry’s two dimensional acculturation model

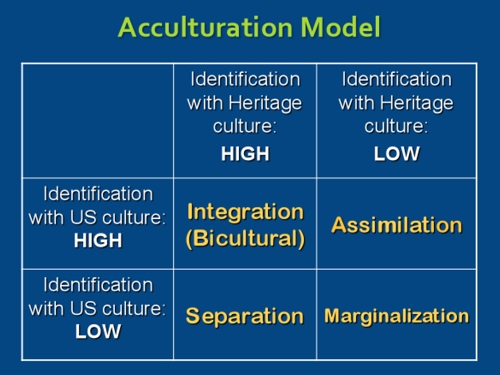

John Berry has a model for acculturation that I find very useful to describe how people adapt to a new culture.. It is very helpful in terms of describing individuals’ experiences but also family experiences and conflicts. In this model we look at a person’s acculturation in terms of 2 dimensions:

- how much does the person seek to maintain connection with the culture of origin? (What is Lily’s attitude toward her heritage culture and identity?)

- how much does the person want to learn and adopt the new culture (What is Lily’s attitude toward learning and interacting with the new culture?)

The two dimensions used to gauge acculturation leads to the following table (sometimes called a 2 x 2 matrix) that describe four ways people may chose to adjust to a new culture.

The 4 ways to adjust to a new culture correspond to 4 different acculturation strategies that people use in response to a new culture.

-

Assimilation

People who consider their culture of origin to not be important and who want to identify and interact mainly with the new culture are said to be using an assimilation strategy. (upper right quadrant of the table)

-

Separation

People who value their heritage culture and do not want to learn about the new culture fall in the lower left quadrant of the table. These people are adopting a separation strategy to acculturation.

-

Marginalization

People who neither identify with their heritage culture nor with the new culture are pursuing a marginalization acculturation strategy. (lower right quadrant)

-

Integration (Biculturalism)

People who seek to maintain their heritage culture and learn from and interact with the new culture are considered to be using the acculturation strategy of integration, or bicultural strategy. (upper left quadrant)

Acculturation strategy and psychological health

These four strategies describe ways individuals respond to the challenge of a new culture and how they adjust. Research on the emotional and mental health of people using the different strategies shows that people who use the acculturation strategy of marginalization are more depressed, anxious and have poorer mental health than any of the other groups. People who use the integration (biculturalism) are the most psychologically healthy (and are more successful) than the other 3 groups. The psychological health of those who use separation or assimilation lies somewhere in between.

Acculturation strategy and family conflict

These four acculturation strategies are ways chosen by individuals to adjust to a new culture. In a group, each individual may chose a different strategy, and may acculturate a different rates. Grandparents may be pursuing a strategy of separation; the father a strategy of marginalization; the mother a strategy of integration and the children, assimilation. Much intergenerational family conflict can arise from this situation. More in another post.

Questions? Want to know more? Ready to take the next step and explore the possibility of working together? Give me a call at (650) 327-3003. I look forward to hearing from you.

Notes:

John W Berry 1997, Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Applied Psychology: An international review 1997 46(2), 5-68.